[สำหรับฉบับภาษาไทยที่แปลและเรียบเรียงโดยผู้เขียนเอง “ข้อคิดหลังดู ‘เดอะ แบทแมน’ ว่าด้วยโรคขยาดความยุติธรรมในศตวรรษที่ ๒๑” คลิกที่นี่.]

Superheroism in entertainment media has next to nothing to teach us about justice. Statements such as this should no longer be controversial in an era where many assumptions about superheroism in the conscious content produced by comic/screenwriters are regularly “critiqued”, sometimes by comic/screenwriters themselves. The Alan Moore school of metacommentary, an erstwhile niche concretized by iconoclastic classics such as V for Vendetta and Watchmen, now enjoys a success as an originary line of household consumer products in western and post-west cultural imagination. A popular characteristic trope of this product line is the portrayal of superheroes and their antagonists through seemingly more human and more nuanced narratives. Morally ambiguous, hyperindividualist, and politically impotent mavericks now stand shoulder to shoulder with repackaged remnants of institutional exceptionalism against threats that mirror them introsepctively yet diametrically. From time to time comic/screenwriters would return to the bestselling theme of justice, each time manufacturing anew both the context for a supposedly universally applicable idea of justice and the contradictions between this universal fiction and the hero’s, that is the writer’s own, subjectivity.

There are quite a few recent mainstream examples of the genre that seem to have exhausted the limits of what metacommentary can offer, at best managing to tail certain currents of western sociopolitical consciousness. Off the top of my head there’s the uselessly self-aware The Boys, produced by an Amazon Corporation subsiduary, in which superheroes are financial assets of mega corporate entities accountable only to the power of major shareholders; Robert Kirkman’s Invincible with its subversion of the Superman tropes; and HBO’s 2019 Watchmen series which continues the story of Moore’s original comic and further explores the mutually beneficial relationship between masked vigilantism and repressive state apparatus. This overall aesthetically grittier take on the genre is often contrasted with the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s more exceptionalist storytelling in the company’s big-budget, high-margin IPs that manages to effectively neutralize complex realworld political questions by maintaining in MCU narratives and simplified analogies an unstated assumption of an absolute good, so that the question of justice is rarely if ever raised. Hence, Stark Industries’s corporate callousness, a main narrative concern in Iron Man, the film that started the entire MCU in 2008, is glossed over in the latest Spiderman trilogy by an overemphasis on the teenaged Peter Parker’s innocent potential[1], and given a redemption arc that culminates with the 2019 Avengers: Endgame when billionaire philantrophiliac and military-industrial contractor Tony Stark, the figure of liberal/libertarian savior fantasy, meets his desired match in the comically genocidal Thanos and finally gets to matyr himself. In these cases, the audience cannot fail to get the sense that saving the world, and by extension the world that is being saved itself, is incidental to the resolution of the protagonist’s various complexes.

The Batman legendarium remains one of the few popular western mythologies that consistently allow writers to experiment with different mixtures of metacommentary and exceptionalism. Notably, USAmerican directors Christopher Nolan and Matt Reeves present two complementary social discourses in their respective Batman films. The Dark Knight Rises tells a cautionary tale about the incapability of ordinary people to understand justice, a dismissal of the then ongoing Occupy Movement, while The Batman appears to counter Nolan’s cynicism by at least placing the dark knight in a subjective conflict between justice and vengeance. Functionally speaking, however, the two presentations only differ quantitatively. Reeves’s moralizing defers the discussion on real and transformative justice indefinitely beyond a vague future promise of change, the effect being similar to Nolan’s absolutist presentation that disregards change as an organic force altogether. We are here dealing with the conservative denial of the motive force of history on one hand, and the liberal nondialectical division between aspects of a contradiction on the other.

What is meant by this nondialectical division? It is that vengeance is assumed to be a matter of course, a natural consequence of justice denied. In the final action sequence, we see one of the Riddler’s mass-shooting reddit friends spit back at Batman his own catchphrase, “I am vengeance”. Whatever lesson the film is trying to teach is undermined from the start by the absence of any voice from an honest working-class perspective. Undermined not so much by its assessment of the potential harm to society when vengeance is taken to the extreme, but by an insistence characteristic of the superhero genre to teach any and all lessons through violences that feel as light as a feather on account of thier excess. Furthermore, as is the case with most other Batman media, there is a fetishization of the social relation between slave and master. The unimpeachable serf Alfred Pennyworth remains in this film the moral cornerstone of the crown prince Bruce Wayne’s existential crisis. Despite how conflicting the narratives about Thomas Wayne are presented, the audience can’t help but feel that the final word is said by Alfred when he reassures Bruce of his father’s incorruptible private virtures. The creative decision to have Alfred defend Thomas’s purity as a person only has radical implications if we keep in mind that Alfred is an unreliable narrator of Thomas’s story, one who refuses to tarnish the memory of his master despite almost being killed himself by an explosive device sent in by the Riddler, a childhood victim of the Waynes’ involvement in the criminal overworld[2].

In the living history of communism, the search for purity, be it ethical or ideological, has had detrimental effects on organizational practice. Academic dogmatists who, upon coming face to face with the reality of protracted struggle, suddenly call for a return to pure Marxism or to the rupturous moment of revolutionary Leninism, to trace a continuity devoid of blood and sweat. This academicism manifests itself in an adventurist attitude toward the masses, the same attitude we see in The Batman’s gaze at the Gotham citizens who are either helpless victims one bad day away from becoming full-blown psychopaths or regressive lumpens unfit to live in civilized society. When the narrative requires that something be said about Gotham’s post-trauma prospects, the audience is reminded from time to time that the mayor-elect Bella Reál will bring Real change to the city. The pun works at a deeper level of irony than it appears, since the psychoanalytic Real is something that the subject does their damnedest to avoid.

The opposite aspect within The Batman’s discourse on justice was already present in the 2005 movie adaptation of Moore’s V for Vendetta. Here, the Wachowski siblings tried to give the masses some semblance of collective agency which was missing from the original comic. The result, however, was a caricature that we had already seen two years prior in The Matrix Revolutions. An unrecognized delusion at the core of western and post-west left imagination exemplified by the denouement in which V’s terrorist strategy miraculously inspires both the living and the dead to stage widespread riots that presumably successfully topple the british government. Later, Lana Wachoski’s fourth Matrix entry would astutely conclude this political impotency of the postmodernist discourse whose trajectory mirrors the series’s regression, from a dream of rebellion against a panoptic reality to a confrontation between online superhumans in an urban chic internet café. How much metacommentary Lana intended for her latest feature film to contain is beside the point. What seems at stake here is the efficacy of metacommentary itself.

In the real world from which the left has retreated, socioeconomic organizing that could lead to transformative political rupture is a lengthy, grueling, and unspectacular commitment that requires direct involvement in the community. The absurd trope of a special clique somehow successfully mobilizing a significant portion of the masses through isolated acts of terror or superheroism is pure fantasy, and its continued proliferation in fiction all over the world since the “end of history” betrays a subjective confusion between imagination and escapism. Variants of this trope in japanese manga/anime industry remains highly marketable with a fresher, sometimes bleaker coat of paint than its western competition. Examples are numerous, from the shōnen staple One Piece, with its sprawling universe that deserves a thorough criticism, to the epic Code Geass about a member of royalty who uses political intrigues to maintain the power structure and legitimacy of his class. One striking moment from the epilogue of Akame ga Kill! bears mentioning for the matter-of-factness with which the narration describes the surplus enjoyment upon exacting revenge on the manga’s antagonist: After the rebel’s army victory against the corrupt government, prime minister Honest is publicly executed by having rebels take turns flensing him, with the minister being kept alive through the whole ordeal. Grewsome ultraleft revenge fantasies of this type have served to denigrate the masses to a degree rarely achieved by conservative excesses; radical dressings of the narrative cannot hide a content severely limited in depth by the media form.

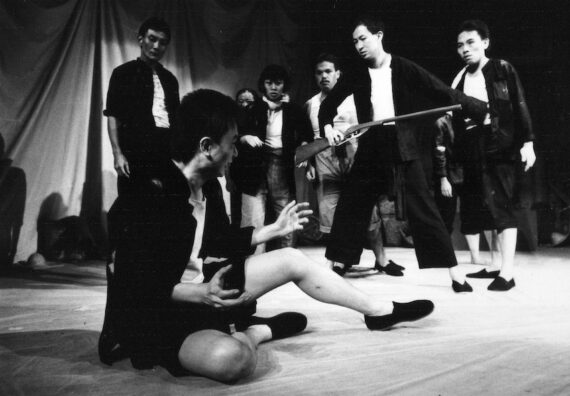

How then do we prepare for our confrontation with real change? The necessity of justice and the impulse for vengeance inevitably exist in a society gripped by oppression. The task is to help a community collectively achieve the former on their own initiative while reckoning with the latter in the process. For glimpse of what is to be done, students of communism of all levels should study the various highly organized social movements in China’s Liberated Areas during the revolutionary period. One of these movements is the 1948 party purification campaign documented in the seminal text Fanshen by Hán Dīng during his time as a university member of the Long Bow Village land reform team. In this campaign, each communist party member has to conduct self-criticism before a metaphorical gate manned by the village population, organized into different leagues and associations. Past crimes and mistakes of each cadre are brought up at public gatherings, grievances freely aired out, cases investigated; and naturally some victims would call for physical retribution or exorbitant recompense against cadres who had beaten or stolen from them. But the point of the movement is to rectify the cadres’ attitude, style of work, and subjective relation to the people, and the team, with the help of reasonable voices among the population, would facilitate the two-way transformation. At this grassroot level there is no institutional judgement, no one to play the role of judge or jury. Suitable repayment to victims, to the community, and whether or not the cadre would be allowed to remain cadre, all this would be determined by consensus reached in public, or deferred to another session after further discussion among the leagues and associations should the case prove especially complicated. More importantly, the criticism process would make the subjects involved “see himself as others saw him.”[3]

It is precisely this mutual seeing that cannot be done from behind a mask, for the mask always signifies an Other who gazes from the safety of an inward outside. Trust in the masses and new possibilities will emerge; be one of the masses and you’ll have nothing to fear.

Fanshen, a play adapted by Davi Hare (1985) https://archive-tworks.org/fanshen/

Fanshen, a play adapted by Davi Hare (1985) https://archive-tworks.org/fanshen/

Endnotes

[1] This is also a recurring narrative in the recent movement for democracy in Thailand. The harsh truth about new generations, however, is that they are neither innocent nor pure, if we are to understand innocence and purity as identifying with “good” liberal/libertarian politics. Many of today’s youths hold reactionary views and/or attitude, and those who don’t rarely recognize the reactionary nature of liberal/libertarian ideology.

[2] Reeves’s film is not the first piece of Batman media with a nuanced portrayal of the bourgeois Thomas Wayne. In the 2016 videogame Batman: The Telltale Series, the senior Wayne acts as an arm of Falcone and the Gotham Mayor’s repressive state apparatus by committing political opponents and investigative journalists to the Wayne Enterprises-funded Arkham Asylum.

[3] William Hinton, Fanshen, (Monthly Review Press, 2008), 466. It should be said that such gates are practical experiments in bottom-up transformative justice. If the severity of the crime goes beyond the local purview, then the offender would be handed over to the higher legal authority of the county court.