[For a Thai-language version “อ่าน ‘สามก๊ก’แบบคนอีโก้สูง,” click here.]

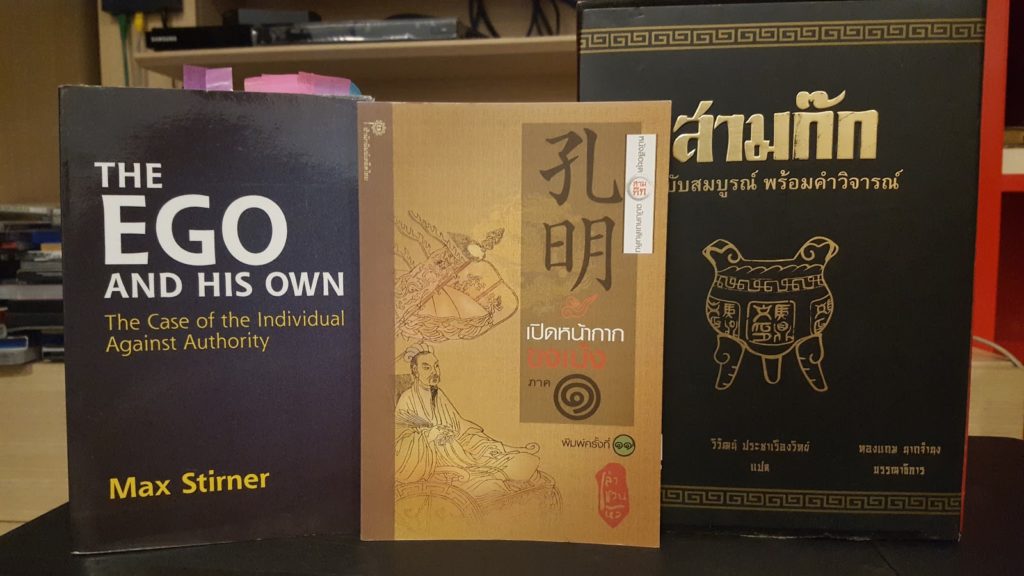

By quite a few people I’ve been asked When did you start reading seriously and what and by who? To this I like to say out of habit It was Edgar Poe in eighth or ninth grade and to sometimes specify the Scholastic pocket collection of his more famous poems I picked up at Seed bookstore at The Mall Bangkae way back when they still ran that Fantasia Lagoon show with volcano and demon holograms and wireflown wizards in gay tunic and no hat gliding wall to wall and no skytrain construction along diamond road or on that side of lords’ river at all. But to stand by this easy answer is to accede still to the mindset I kept so as to remain insane through AFAPS’s bleakly sobering years: that the higher the degree of escapism, the more serious the literature. Indeed, under prescribed conditions of intellectual and moral subservience, few distractions proved able to alienate me from my immediate actuality and at the same time tease a connection to some world out there as effectively as the Weird genre of fiction. However, my discovery of Max Stirner prompted a reexamination of my literary interest previously thought of as no more than a hermit’s pastime.

Stirner’s brand of individualism as a whole tickled Marx’s testicles to the point that a large portion of The German Ideology was dedicated to criticizing The Ego and Its Own for its blanket dismissal of all that is holy, including the proletarian consciousness. Sanctity, Stirner proclaims in Ego, is the first enemy of the individual that must be destroyed. Be it that of kings or congressmen, of royal decrees or democratic consensuses, of rights by god given or by state legislatured, of religion or irreligion, and so on. To students of Stirner, the concept of property is as violable as any of the five buddhist precepts. It is not difficult to see how Marx’s vitriolic retort played right into Stirner’s condemnation. My own reading of the text brought into new light certain passive qualities I possessed as a cadet—unconfrontational insubordination, apathy toward royalist patriotism, and so on. To those whom I here deem my detractors of old, these qualities were inexplicably different from those exhibited by the regular class delinquents who would actively challenge their superiors then later assume the legacies passed down from the same superiors through some loopholes in AFAPS cultural rules.

Upon so clear an affirmation aroused in so vague a human being as the amateur reader, it is not difficult to imagine how tempted one such specimen can be to embark suddenly, and possibly without return, on a Stirnerite search for or placement of the literary self within one’s existential makeup. A work of literature must now be merited not on the basis of its capacity for escape, declares the proselyte, but on the basis of its incremental contribution to the ultimate exorcising of any and all reverence from man’s ontology. And, by this criterion, the more appropriate question to ask now becomes When did literature first sow in you the seed of subconscious belligerence and by what means, if the course of such a development is at all traceable? My answer this time: Probably after the second or third reading of Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Pracharuengwit’s edition with royalist commentary) and subsequent introduction by a fellow AFAPS undesirable to one chinese-thai critic by the nom de plume Lao Chuon Hua.

Originally written by Ming playwright Luo Guanzhong as a dramatic retelling of the history of the late Han period as recorded by Jin historian Chen Shou, the chinese epic continues to enjoy worldwide readership for its timeless aestheticization of state violence and instances of strategic brilliance that supposedly still apply to modern political and military warfare. The obvious protagonists of the novel are the Shu Han, a Han remnant dukedom founded by Liu Xuande, a cobbler and distant relative to the Han emperor; while the other two factions, Cao Wei and Sun Wu, are portrayed as villainous usurpers and inconsequential parvenus respectively.

The novel has undergone countless mutations across all forms of media, but the religious deification of Shu Han warlords, blown out of proportion by the novel’s uncritical popularity, is still alive in china and thailand to this day.

In response to unchecked Shu Han sanctity which he deemed a harmful component of chinese-thai morality, Lao Chuon Huo wrote the nine-volume ROTK Commoner’s Edition, an edition unlike most others available in thai in that, instead of giving the same chronological narrative from The Yellow Turban Rebellion to Sima Yan’s ascension, it deconstructs plot points and character motivations using Chen Sou’s records as the primary reference. To wit, the Commoner’s Edition is an endeavor to return myths to history or reduce them to bad fan fiction, a task that runs counter to Luo Guanzhong’s original nationalistic intent for the novel.

Having stripped away melodrama and found tall tales devoid even of the slightest truth, Lao Chuon Huo took scathing liberties with fictional events that defined Shu Han characters‘ divinity in the chinese pantheon. The one hundred thousand loyal peasants who refused to abandon Liu Xuande during his flight from Xinye are revealed to be human shields used to deter Cao Wei’s pursuit; Zhuge Kongming’s seven captures and seven releases of the stubborn king Meng Hou, traditionally construed as the God of War’s1 seven attempts to win over the Nanman people, are actually seven rounds of Nanman genocide to secure Shu Han’s southern border; Guan Yunchang’s adamant refusal to return Jingzhou to the Sun Wu, who had loaned the province to his sworn brother Xuande in goodwill, is now seen as a diplomatic failure by bravado that led to the loss countless lives including Yunchang’s own in an otherwise avoidable conflict; and so on. Consequently, some legitimacy of the dominant Cao Wei government was restored. Yet so reviled still is the faction that dedication poems to prominent Wei statesmen remain excluded from standard editions of the novel, their civic deeds eclipsed by drama subplots fit for chinese opera or HBO.

I have no knowledge of Lao Chuon Huo’s politics beside comments in an author’s note to the effect that he believed the novel responsible for the corruption and downfall of the indigenous chinese by the Manchurian Qing, a sentiment for which critics have called him a communist. His feelings about this label are also unknowable, but one gets the sense that he doesn’t have much respect for the race of submissive consumers of literature.

Unfortunately, by the time I first read the Commoner’s Edition, I had progressed past the schoolyear when the myth of Zhao Zilong’s heroism at Changban was a required reading in the thai class as prescribed by the ministry. Would have liked to knock Ms. Atshara down a peg or two.

Who was your Lao Choun Hua? Who was your Stirner? In this faithless spirit I leave these questions and others aforesaid to you, my fellow delinquents-turned-deicides or aspirants to such dignity, and eagerly await no one’s answer.

Dion de Mandaroon

1 I consider the Sleeping Dragon to be more deserving of this title than Honest Guan on account of the active role he played in realizing his proposal of a divided china. The Nanman example here given is but one of his last prime-ministerial achievements.

พีระ ส่องคืนอธรรม แปล