[สำหรับฉบับภาษาไทยที่แปลโดยผู้เขียนเอง “ศักย์หลุดพ้นในการเล่าเรื่องของวิดีโอเกม: บทใส่ความย้อนหลังให้โจ๊กเก้อของคัทซึระ ฮาชิโนะ” คลิกที่นี่.]

Two films in 2019 have got all the left talking. In the far east Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite emerged as a masterpiece in class drama that takes black comedy, mystery, ultraviolence, and melancholia1 to their most effective extreme. Having watched Parasite first, Todd Phillips’s Joker felt to me almost like an afterthought. Indeed, certain characteristics exclusive to the south korean lower class, particularly the poor’s attitude towards the rich and the ideological solidarity between the two classes facilitated by good eastern patriarchal manners and by what is notionally accepted as fair wages, seem to place the Kim family at a level of subjugation even deeper than that experienced by the Fleck family. One that, like lobotomy performed on an institutionalized undesirable, curtails any possibility of subjectivization after trauma, as shown in the film’s conclusion where Kim Ki-taek, the father of the poor family, profusely apologizes to a dead Park Dong-ik, his rich counterpart whom he fatally stabbed after a chain of events that led to the death of Ki-taek’s daughter, and himself returns to the underground bomb shelter hidden not twenty meters away from the scene of the crime to hide from the authority possibly for the rest of his life.

Owing to the twist the film gives to an established western comic canon and the political climate engendered by the latest escalation of neoliberalism in the form of the Trump presidency, the western left understandably has much more to say about Arthur Fleck. In his essays on Joker (2019) 2, slovene philosopher Slavoj Žižek discusses at length the idea of authenticity and identification. Žižek places the public’s fascination with the Joker in the appeal of the mask. The multifarious and nigh mythical figure of Joker in the Batman legendry can only be found in this mask and not in the person behind it. To be sure, the violence enacted by both the Kim family and Arthur Fleck is symptomatic of an impotence, but whereas the latter is not portrayed as a figure for the audience to identify with, the former does not resist identification. Joker’s dark vision, Žižek claims, wouldn’t have succeeded as a cinematic experience without the overlaying fantasy structure of the Batman legendry to sustain the film’s realism. And yet the even darker vision of Parasite works without any reference to a fictional universe. This is because the realism of Parasite has the underlying structure of what I would call urban neo-gothic fiction. An inaccessible estate isolated from the lower world by high walls and trees, a forbidden romance, a murder cover-up, lights that flicker as if with a will and meaning, an apparition that haunts and stares from the dark of the cellar. These are adapted tropes that could fit comfortably in any classical gothic framework.

But what about authentic and not so impotent figures of radical potential that invite identification? Such figures in cinema who possess one or two of the virtues ultimately must maintain their effectiveness from a distance, through a lack. Without the contour of this lack cinematic study of these characters would prove disastrous: Christopher Nolan’s Joker with a working-class or military3 origin story, Travis Bickle cleaning the streets of New York as a progressive policymaker for Charles Palantine, V that in death reveals to the audience the face under the Guy Fawkes mask, etc. An effective portrayal of the complete triune, I claim here, requires a more engaging medium than the silver screen.

In 20164, japanese videogame developer ATLUS released their latest flagship roleplaying title, Persona 5 directed by Katsura Hashino. Its subsequent english release in early 2017 garnered attention from the western gaming community at large in part because the release seemed to coincide with the US presidential election. A trademark of the series is its duality in narrative setting and gameplay. The typical Persona protagonist lives a normal japanese highschool life by day and explores a sinister alternate reality by night. As each entry’s distinct story unfolds, the player navigates the protagonist through both worlds, aiming to excel in midterms as well as boss battles. What I find most interesting about the series is the player’s subjective relation to the main character, which cannot be understood in the terms of D&D design philosophy of western roleplaying or the popular japanese form in the vein of Final Fantasy. Here the player doesn’t assume Cartesian subjectivity of a highly customizable character within a gameworld that promises consequential “free” choices or a fantasy Other that, in its utter otherness, imposes itself onto every facet of the narrative on the player’s behalf.

Identification with the Persona protagonist is forced; some ATLUS titles even prevent the player from starting the game without acceding to a metacondition. A recurring motif at the beginning of every title in the series involves the protagonist signing a contract or agreement of some sort, at which point the player is prompted to perform their only truly free action in the game, which is to name the protagonist. Precisely at this moment of christening the hero usually gains the power to access their eponymous Persona, their myriad mask, and control is then relegated to the player in earnest. This awakening at identification is not a coincidence. In Persona 5 especially, the introductory scene takes on an emancipatory implication: The player sees the as yet unnamed protagonist, identified in an earlier scene by his nom de masque Joker, being brutally beaten and drugged at the hands of police interrogators into confessing his crimes and revealing the names of his 5 comrades. But the only name he gives, the name the player is asked to fill in, is his own. To wit, and I think here is an oft overlooked stroke of genius unique to this series, the player is the protagonist’s authentic self.

As the name of the series suggests, the thematic underpinning of the Persona universe corresponds decidedly, hence embarrassingly, with Jungian mysticism. Personas function in the gameworld’s alternate reality as spirit-like personifications of their users’ psyche, categorized into the Rider-Waite major arcana according to the character’s social relationship to the protagonist who himself is the wild card, The Fool, capable of switching between multiple Personas. The series’ famous spoken quote 6 suggests Personas emerge from “the sea of thy soul”, an equivalent of the collective unconscious. This explains why they take the forms of figures from realworld myths, legends, religions, and works of fiction 7 whose archetypes match those of their particular Persona-user’s. In the fifth title, members of a conspiracy of social elite project a distorted cognition of the real world. These projections constitute the gameworld’s alternate reality in which reign Shadows, subconscious embodiments of drive. Joker and friends, highschoolers who awaken their Personas through rebellious and painful identification with the mask, navigate this alternate reality in the guise of Phantom Thieves of Hearts with the stated goal of social reform by, quite literally, stealing and thereby changing the hearts of the corrupt elite.

Ontologically speaking, the cognitive world of Persona 5 does not exist at a lower level than the game’s reality of Shibuya Japan. Setting aside the game’s sci-fi/fantasy internal logic, there is a nice resemblance in the Thieves’ method of reform to clinical psychoanalysis. Bruce Fink writes, “[P]art of the psychoanalytic process clearly involves allowing an analysand to put into words that which has remained unsymbolized for him or her, to verbalize experiences which may have occurred before the analysand was able to . . . formulate them in any way at all.” 8 What is stolen from the Shadow’s seat of drive appears to Joker at first to be nothing more than a swirling of colors. This formlessness, usually the antagonist’s anchor to a trauma event, becomes a tangible object that the Thieves may take with them back to the physical world only after the Shadow is defeated and forced to verbally reckon with the trauma. Afterwards the antagonist’s ego-self suffers a complete breakdown and confesses their crimes to the public.

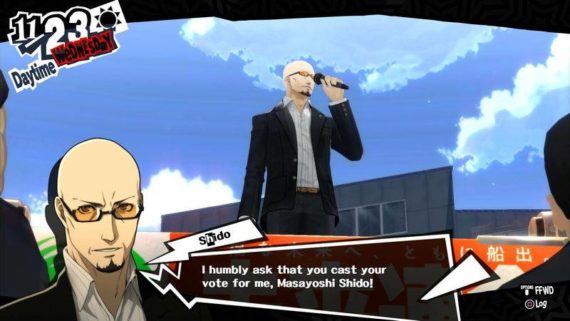

So what message is Persona 5 telling us regarding the reformist position in which we can imagine neither the Kim family nor the clown-masked protesters at the climax of Joker 9? Persona 5 goes perhaps one step further and forces the audience/player to reckon with the unspoken failure that gives rise to its central human villain, prime minister-elect Masayoshi Shido. A charismatic nationalist populist, Shido’s promise of societal reform in his election campaign towards the end of the game parallels the Thieves’ own desire Despite Shido’s eventual defeat, the true horror begins to dawn upon Joker and the Thieves when, after Shido’s nationally televised confession to his part in the conspiracy and to the existence of the conspiracy itself, polls show no sign of decline in the public’s support for Shido and his party. The general public, graphically portrayed most prominently as suited hunchbacked faceless commuters in the background, has already included in its conscious discourse a suspicion of Shido. But dialogues between minor NPCs show that it only speaks of this suspicion in the language of controlled representation. Shido’s defeat only brings to the forefront what the player already knows about the extent of the conspiracy: media moguls, private financiers, law enforcement agencies, tech monopolies, members of the nobility, and so on. In other words, there is no conspiracy at all insofar as conspiracy is categorically understood by unknowability. Hence the player through the Phantom Thieves, themselves a revolutionary vanguard of sort, returns to the Marxist-Leninist formulation: The repugnant battlefield of liberal electoral democracy cannot be left uncontested. Naturally, at this juncture in the narrative the game is forced to come up with a true final boss, a painfully typical metaphysical god of control, to explain away the final act whose resolution is nothing short of emblematic of our realworld predicament.

In the way Persona 5 confronts the public’s overemphasis on truth in its misleading particularity, on individual confessions of corrupt public figures, can we not discern the modus operandi of Julian Assange? Can we not call him — who at this very moment awaits in brutal suffering his extradition to the US for the legal crime of informing the Other of its own crimes against humanity — a true Phantom Thief of Heart? Isn’t the spectacle attending such inquiries as the Trump impeachment hearing, the OAS’s allegation of fraud in the latest Bolivian election, and the ousting of Thanaton J. from the thai parliament, distracting us from the total picture? When a member of the Phantom Thieves awakens to their Persona, they keels over in excruciating display of pain and liquid black inexplicably seeps from their eyes as if their self can no longer tolerate it. In times of despair I like to remind myself that there is no such thing as a political life in that it is not life itself but a life reflected back to us from this excess of black void. Look closely at it pooling. The very shape portends terrifying possibilities indeed.

Footnotes

1 Here I emphasize the socioeconomic aspect of the Kim son’s despair. His father’s redemption hinges on the realization of an elementary fantasy shared by many of the asian urban poor that one day they would become rich enough to buy a big house. Many critics have read the son’s letting go of the Feng Shui Wealth stone, the weapon used to bludgeon him to near death, as a symbolic letting go of wealth for wealth’s sake. This reading lacks a dimension familiar to students of Lacan. The son’s cause of desire for wealth simply shifted onto the imagined desire for release of his father, a desire which the father himself never expresses to the audience.

2 Slavoj Žižek. “More on Joker: From Apolitical Nihilism to a New Left, or Why Trump is no Joker.” The Philosophical Salon, http://thephilosophicalsalon.com/more-on-joker-from-apolitical-nihilism-to-a-new-left-or-why-trump-is-no-joker/.

3 A popular fan theory extrapolated from the Joker’s conscious discourse with the Harvey Dent character during the hospital scene.

4 In the course of my duckduckgoing in search of an appropriate title for this article, I found that Joker (2016) would indicate an already existing tamil film which incidentally deals with brutal socioeconomic inequality.

5 There’s a reason for my shift in pronoun usage here. While the flagship releases only have male main protagonists, a remastered release of Persona 3 allows gender choice for the lead character.

6 In full, “I am thou. . . Thou art I. . . From the sea of thy soul, I come. . .” followed by lines specific to each Persona.

7 Entities from the Lovecraft Mythos first appeared in the series as early as Persona 2 (1999), not to mention in other ATLUS IPs rarely released outside japan such as Shin Megami Tensei.

8 Bruce Fink. The Lacanian Subject. Princeton University Press, 1997, 25.

9 Figures of impotent psychopathy like Arthur Fleck also exist in Persona. Police detective and serial killer Tohru Adachi from the fourth entry is the most notable example.