[สำหรับฉบับภาษาไทยที่แปลและเรียบเรียงโดยผู้เขียนเอง “คอสมิคฮอร์เร่อ (Cosmic Horror) กับข้อคิดไปเรื่อยว่าด้วยคอมมูนิสซึ่ม, วรรณคดี, และเฮ็ด.พี. เลิฟคราฟท์” คลิกที่นี่.]

Whatever the historical demerits of Trotskyism might be, of late I have been obliged to recognize my own political assumptions by the fact that one of my most favorite authors is the late Joel Lane, weirdist and active member of the Troskyist Socialist Party of England and Wales, whose fiction is informed by an empathetic connection to the working class of Birmingham UK. Lane’s output in the Lovecraftian tradition manages to subvert the popular conception of cosmicism as cynically disinterested and antihumanist by rooting conflict in social(ist) realism as opposed to the usual Lovecraftian brand of contravened mechanistic realism. Here, the choice of which realism to use is not only a question of literary technique or artistic form, but also a political one. Some comrades have reminded me of the relation between revolutionary practice and socially-informed artistic sensitivity. Asanee Balachandra, under the name Indrayudh, translated from chinese the Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art by Mao Zedong in the hope to shake up progressive art and literature in the country that would be known as Thailand; and it was because of their radical engagement with literature that Chit Phumisak was suspended from Julalonggorn University in 1954 and Joseph Stalin was expelled from the Tiflis Theological Seminary in 1899. So, how did the Soviet hope for the future came to be associated with the static kind of socialist realism, with artistic production that seemed to supplement in function the numberless literature on “real conditions” of the USSR written by its visitors and escapees, reverers and detractors alike?

An easy leftist response would be to chalk it up to the Cold War discourse. Legitimacy is a game so cheap any sucker can buy in with chips as worthless as the one on their shoulder. But real effects occur because of real mistakes made where the stakes are much higher. In a speech delivered to students of the Communist University of the Toilers of the East on the relationship between proletarian and national culture, Stalin based his understanding on the assumption of two basic elements of cultural production: form and content.[1] What he did not take into account as a third element, in contrast to the priority of the Soviet avant-gardists[2], was the process of production itself. The omission of this third element, when extrapolated to the political practice of the Soviet Union under conditions of the Second Time of Troubles[3] , may in part serve as a metaphor for the ensuing ossification of the Soviet bureaucracy. Thus, social(ist) realism functions for Lane at the level of production, whereas, along a certain Party line, for the mainstream Soviet intellectual it ceases functioning and becomes a mode of representation.

Paradigm

Likewise, discussions among the thai H.P. Lovecraft fandom have gone no further than his supposedly undeniable influence on genre horror in western popular culture. A general attitude of nigh-mystical genuflection toward the “philosophical” content of Lovecraftian fiction – that is, with cosmic horror – hinders any critical examination of Lovecraft as author and human being beyond rote reference to biographical facts or to praises sung by his or our contemporaries. By inextricably tying the content of cosmic horror, or cosmicism, to Lovecraft’s subjective understanding of the world and universe at fixed points in his life and career, the reader risks mistaking a single representational paradigm for the whole of what the weird genre of fiction has to offer.

The existence of other cosmic paradigms isn’t a modern invention made in perfect hindsight. Lovecraft himself detected a subjectivity antithetical to his own in the works of british weirdist William Hope Hodgson, even though they both wrote in roughly the same form and engaged with the same “philosophical” content. One of the weirdists whose revival rode in on the coattails of the Lovecraft renaissance, Hodgson created a unique cosmic vision as uncompromising at its height as that of Lovecraft or any other who would later write in the Lovecraftian tradition. Yet, when faced with the radical Unknown, his characters can rarely be characterized primarily by passivity or terror. Where the typical Lovecraftian intellectual protagonist plays the role of observer or willing victim, Hodgson’s supernatural detectives, soldiers, and sea captains actively struggle against their doom, with failure and success in equal measure. Indeed, Lovecraft himself thought that this “commonplace” and “romantic” sentimentality was a creative tendency that undermined Hodgson’s novels The House on the Borderland and The Night Land[4]. Contradictions in what we know of either weirdist’s life experience bear out this contradiction in their subjective relation to the cosmos. While Lovecraft agreed in 1926 to commission a long essay on the history of superstition[5] for Harry Houdini, for whom he had ghostwritten the short story Imprisoned with the Pharaohs in 1924; on 24 October 1902 Hodgson had challenged and almost defeated Houdini’s escape trick, managing to keep the magician struggling with restraints of his own design for no less than 45 minutes[6]. Even more notable is the matter of World War I. Around the time that Lovecraft was reiterating the myth of human’s warmongering nature and waxing fascistic about the temporary embarrassment of the teutonic people who had been duped into fighting among themselves by inferior races[7], Hodgson had served for more than two years before he was killed in action on the field of Mont Kemmel. A eulogistic attribution by his commanding officer bears considering:

“Of his courage I can give no praise that is high enough. He was always volunteering for any dangerous duty, and it was owing to his entire lack of fear that he probably met his death on April 17. ”[8]

Even a casual noncomparative reading of Lovecraft could yield a cosmic horror vastly different from its popular conception. Recall his famous self-deprecation in a 1929 correspondence with Elizabeth Toldridge, ‘There are my “Poe” pieces & my ”Dunsany” pieces – but alas – where are my Lovecraft pieces?’[9] In fact, by that time Lovecraft had already laid the foundation for what would be his original body of Lovecraft pieces. The creative energy with which he would produce The Call of Cthulhu was unleashed after his hysterical flight not from a risen alien god or a glimpse into a transcendental geologic vastness, but from a failing marriage and the ethnic diversity of New York City in 1926. This paradigm primarily characterizes cosmic horror with repressed impotence, not awesome universal fear[10].

Process

Just as reliance on representation in democratic processes stifles political participation and consciousness, if there were to be such a thing as socialist continuity in weird fiction, the socialist weirdist could base their creative impetus on social participation in, rather than private representation of horror. What is meant by this participation, this process?

The novella The Return of HPL by Nop Dararat imagines an ideal scenario in which Lovecraft comes back to life, with much media fanfare, to finish a new novel in our time. Although the resurrection raises an interesting question about the way Lovecraftian fiction participates in today’s world, it seems at odds with the self-ironic reenactment of esoteric cults in the Lovecraftian commodity niches. Participation in the latter demands private libidinal and monetary investment around a “forbidden” text which every cultist can recite but is rarely seen being engaged with in other manners. At the panel discussion on Lovecraft’s legacy organized by Time Publishing at the 27th Book Expo Thailand this past October, I was struck by one speaker’s remark that you don’t need to read Lovecraft’s fiction to understand its essence, that there are now other ways to directly extract and appropriate the kernel of cosmic horror. Unprepared for such nonchalance and still internally handicapped by grengjai-ness[11], I failed to raise an objection. Regardless, we can see that when representational content is all that is required to enjoy Lovecraft, the simple act of reading as a process, because it is no longer necessary, becomes subversive in both the fetishized universe and the cult metaphor.

To be sure, much scholarship has been devoted to studying Lovecraft’s beliefs, reactionary and backward even by the standards of his time, and the way he sublimated them into his superficially apolitical fiction. In Lovecraftian Proceedings No. 3, Ray Huling’s “Fascism Eternal Lies: H.P. Lovecraft, Georges Bataille, and the Destiny of Fascists” offers a cosmic paradigm that revolves around the dialectics between sacredness and disgust in Lovecraft’s fascination with fascism, while Fiona Maeve Geist and Sadie Shurberg’s “Correlating the Contents of Lovecraft’s Closet” provides a comprehensive discussion on his racism and sexuality. And, of course, S.T. Joshi’s The Decline of the West remains the authoritative text on Lovecraft’s political and philosophical development. Most of the existing studies, however, are done without the benefit of dialectical materialism, as if to mirror Lovecraft’s own obstinate aversion to Marxism, a position on which, at first glance, he gave even less ground than his opinion on fascism and Nazism. He consistently expressed this obstinacy through his belief in the clear division between intellectual and manual labour, and refusal to acknowledge western colonialism as anything but beneficial to colonized peoples. The former was a point of debate with Robert E. Howard in a September 1933 correspondence[12], and the latter case was still being made to the the texan fantasist as late as 7 May 1936[13]. It is tempting to judge based on the material and social conditions that kept him holding firmly onto the two ideological positions. We should resist this reactionary temptation and constantly remind ourselves that the subject is a process.

Such international projects that would erupt in the latter half of the 20th century as the countless revolutionary national liberation movements would be unthinkable to the Lovecraft whose most characteristic works were written in the historical period before the barbaric culmination of Western Enlightenment, whose “last-minute advocacy for socialist policies . . . had only practicality to recommend it, not ethical value” according to Ray Huling[14]. But his turn could only be last-minute if Lovecraft had known that he was going to die in 1937 and had a vested interest in preserving his posthumous reputation. It would be less cynical to regard his gradual shift toward socialism as an aborted process. Lovecraft wrote his last work of fiction The Haunter of the Dark in November 1935. Correspondence around that time suggests that he was a supporter of the New Deal as a reform toward a socialist utopia[15], sharing his practicality-driven socialism with national-chauvinist characteristics with the pre-War political program of major socialist organizations such as the Austrian Social Democratic Party and the Jewish Labour Bund. His late open acceptance of the term socialism contrasts sharply with his ideology during the creative period after The Call of Cthulhu, when he went even as far as to suggest that “the widespread dissemination of rudimentary knowledge produced an unstable emotional equilibrium wholly destructive of traditional forces of life.”[16] Precisely because Lovecraft was an urbanite who took no active part in either the rural or urban productive life, we may read in the stories The Colour Out of Space and The Dunwich Horror, written in this period, a weird mediation between communal superstition and the american university institution imposed upon rural New England as a source from which the “forces of life” may generate a realism outside the reality of industrialisation.

In communist practice, a progressive rapturous moment follows a round of principled self-criticism, a milestone in the development of people and things. We can identify a similar moment for Lovecraft in one of his last letters, written just a month before his death. Here I quote an illuminating passage:

“Well - I can better understand the inert blindness & defiant ignorance of the reactionaries from having been one of them. I know how smugly ignorant I was - wrapped up in the arts, the natural (not social) sciences, the externals of history & antiquarianism, the abstract academic phases of philosophy, & so on . . . God! The things that were left out - the inside facts of history, the rational interpretation of periodic social crises, the foundations of economics & sociology, the actual state of the world today & above all, the habit of applying disinterested reason to problems hitherto approached only with traditional genuflections, flag-waving, & callous shoulder-shrugs!”[17]

It is thanks to this moment after Lovecraft began to identify his disinterestedness, a foundational aesthetic of cosmic horror, with ignorance and libidinal investment that we can retroactively find Lovecraft at his most speculative: What would have changed in regard to cosmic horror, preserved in form and reinterpreted in content by the wave of authors before the New Weirdists, had Lovecraft lived to produce more fiction after his self-criticism? For students of communism and weird fiction, further studies of Lovecraft’s political subjectivity will continue with the long-awaited collected correspondence with his close Troskyist friend Frank Belknap Long, forthcoming in 2023 with Hippocampus Press according to Joshi’s blog.

When last I wrote about HPL[18], I did pass the judgement of “limited imagination” based on Alain Badiou’s poetic category of the soldier which Lovecraft failed to be in real life. As if I was trying to punish my teenage literary idol for lacking the courage to follow through with his pessimism, which manifested as purely metaphysical in his fiction but revealed itself to be ideological and hyperreactionary in his other writings. The picture I discovered after delving into his later correspondence is much more dynamic. And for all his hatred of “orthodox communism” and his “fear of the unknown”, a concession in the middle of his usual polemic against the October Revolution hints that later in life he was not at all averse to new possibilities and was willing to confront them, albeit at his own pace and on his own terms:

“Whatever upturn may come, the cataclysm of 1917 was a tragic set-back which can scarcely be neutralised in a century’s time. The only advantage gained by artists in the upheaval is a sense of the future in civilisation. That’s what the bolsheviks have which we haven’t. They are at the beginning of an era - however poor & lopsided an one,-whereas we are at the obvious end of an era . . or at least of a distinct phase of an era.”[19]

Endnotes

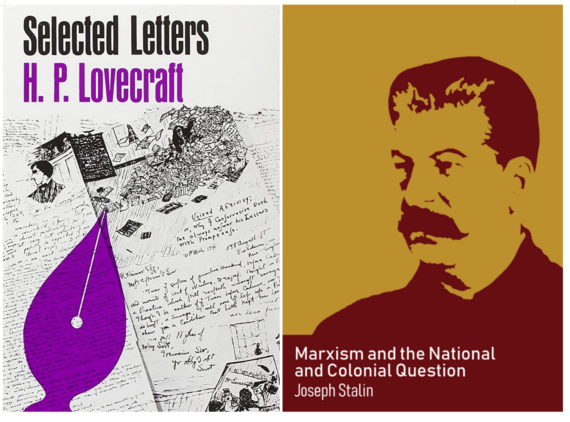

[1] Joseph Stalin, “The Political Tasks of the University of the Peoples of the East”, Marxism and the National and Colonial Question, (Foreign Langauges Press, 2021), 200.

[2] See Saroj Giri’s introduction to K. Murali (Ajith)’s Of Concepts and Methods: ‘On Postisms’ and Other Essays (Foreign Languages Press, 2020).

[3] Refers to the period from the founding of the first Soviet Republic to 1937 during which the Soviets had to defend themselves from foreign invasions and domestic counterrevolutionary forces, analogous to the earlier crisis in 17th century Russia. See pages 90 – 91 of David Ferreira’s english translation of Stalin: The History and Critique of a Black Legend by Domenico Losurdo (Original title Stalin. Storia e critica di una leggenda nera, published in Rome by Carocci).

[4] See Sam Gafford’s blog post The Weird Work of William Hope Hodgson by H.P. Lovecraft (https://williamhopehodgson.wordpress.com/2012/08/01/the-weird-work-of-william-hope-hodgson-by-h-p-lovecraft/) where Lovecraft’s essay “The Weird Work of William Hope Hodgson” is transcribed in full. It originally appeared in the February 1937 issue of the fanzine The Phantagraph, though Lovecraft had discovered and intended to write about Hodgson as early as 1927.

[5] See Alison Flood’s article “Lost HP Lovecraft work commissioned by Houdini escapes shackles of history”, published 16 March 2016 on The Guardian (https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/mar/16/hp-lovecraft-harry-houdini-manuscript-cancer-superstition-memorabilia).

[6] See Sam Gafford’s essay “Houdini v Hodgson: The Blackburn Challenge” in Hodgson: A Collection of Essays by Sam Gafford (Ulthar Press, 2013).

[7] See the essays “The Crime of the Century” (April 1915) and “At the Root” (July 1918) in Collected Essays: Volume 5: Philosophy; Autobography & Miscellany edited by S.T. Joshi (Hippocampus Press, 2006).

[8] My emphasis. See Sam Gafford’s blog post The Life of William Hope Hodgson - Part 8 (https://williamhopehodgson.wordpress.com/2013/06/14/the-life-of-william-hope-hodgson-part-8/) and essay “WHH in WWI” in Hodgson: A Collection of Essays.

[9] HPL, Letter to Miss Elizabeth Toldridge dated March 8, 1929, Selected Letters II. 1925-1929 edited by August Derleth and Donald Wandrei, (Arkham House, 1968), 315.

[10] Adding to the confusion about authenticity, the actual Lovecraft pieces would later become the basis for the revisionist Cthulhu Mythos of August Derleth, who claimed an uninterrupted continuity from Lovecraft‘s legendarium, yet did not share his metaphysics of idealist materialism.

[11] Grengjai-ness fits into the first type of liberal thinking process. See Mao Zedong’s Combat Liberalism.

[12] Robert E. Howard’s letter to H.P.L. circa September 1933, A Means to Freedom: The Letters of H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard Volume 2 edited by S.T. Joshi; David E. Schultz; and Rusty Burke, (Hippocampus Press, 2011), 651.

[13] HPL’s letter to REH dated May 7, 1936, ibid., 929.

[14] Ray Huling, “Fascism Eternal Lies: H.P. Lovecraft, Georges Bataille, and the Destiny of Fascists”, Lovecraftian Proceddings No. 3 edited by Dennis P. Quinn, (Hippocampus Press, 2019), 87.

[15] See, for example, letter to Clark Ashton Smith dated September 30, 1934, in Selected Letters V. 1934-1937 edited by August Derleth and James Turner, (Arkham House, 1976).

[16] HPL, Letter to Berneard Austin Dwyer circa June 1927, Selected Letters II,132.

[17] HPL, Letter to Catherine L. Moore dated February 7, 1937, Selected Letters V, 407.

[18] Dion de Mndaroon, “Beyond Azathoth: Lovecraft Before the Real” (https://readjournal.org/news/17008/).

[19] HPL, Letter to Miss Helen V. Sully dated March 5, 1935, Selected Letters V, 115. A specific point of specualtion here would be Lovecraft’s opinion on Soviet culture after World War II, when participation in literary and other types of creative associations became a common and important part of life in a developed Soviet community. For example, see Joseph Garelik’s A Soviet City and Its People (International Publishers, 1950) for a general account of postwar life in the Ukranian town Dnieprodzerzhinsk and some interviews with its citizens.