[For a Thai-language version “มนุษย์ล่องหน คนอันตรธาน ในจักรวาลของแอมโบรส เบียซ,” click here.]

Monarch, n. A person engaged in reigning. . . . In Russia and the Orient the monarch has still a considerable influence in public affairs and the disposition of the human head . . .

Monarchical Government, n. Government.

—The Devil’s Lexicographer, The Devil’s Dictionary (Hell [or New York]: Dolphin Books), 139.

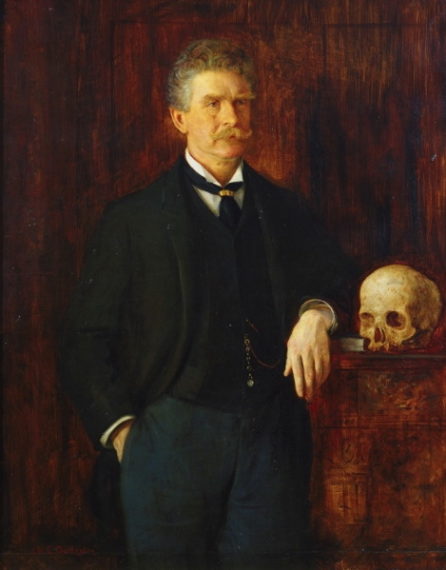

Ambrose Bierce (1842-?)

Ambrose Bierce (1842-?)

In satira veritas. There is an old joke about the rich man who bemoans, “I can’t stand to see these cripples and beggars in the streets. Cart them off somewhere else at once!” Does this rich man not speak for the welloff and the not so welloff in this here city of gods, and even doubly so for prince Siddhartha who, on his first step toward buddhahood, said to his slaves, “I can’t stand to see these cripples and beggars in the streets. Cart me off somewhere in the wilds forthwith!”? The question here is Why the fuck does it fall on satire to deliver vital truth? Among the academically accepted progenitors of the weird genre, Ambrose Bierce stands out as one who succeeded also as a moral witticist.

Students should already be familiar with Bierce, whose classic titles such as The Damned Thing, The Inhabitants of Carcosa, and Haïta the Sheperd exhibit pre-Lovecraft cosmic horror archetypes. But so vast was Bierce’s writing career that his legacy in the mainstream canon can be felt even by the common enthusiast in american fiction. A Union veteran of the civil war and newspaperman during the height of american yellow journalism1, Bierce specialized in short fiction, varying his production from war tales to supernatural stories to literary hoaxes. The latter he sold as sensational newsstories to William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner which counted among its contributors american luminaries Jack London and Samuel Clemens of the Nevadan Sagebrush School.

Bierce’s hoaxes report strange disappearances told by very credible witnesses: A man running a marathon dissolves into thin air right before the finish line, a whole family vanishes one night in their own home, a farmer trips and falls while crossing a field but nothing and no one is ever seen getting up from the spot, and so on. These stories soon passed from print to words of mouth, became urban legends with uncertain origins. Bierce bore hard upon the average american media consumer to confront their own duplicity.

While the uninitiated may be tempted to give these stories a science fiction reading2, the weirdist perspective can perhaps better analogize the despair felt by an Oriental specimen whose head is ever subject to disposition. Through the government, the thai monarch has achieved the same impersonal indifference, the same natural unaccountability characteristic of the cosmic forces behind Bierce’s hoaxes. What really happened to those people? Why them? Am I also going to suddenly cease to exist? There are no answers to these questions either in the case of the marathon man, the Spook House family, the farmer who tripped, or in the forced disappearances of thai political dissidents.

But the weirdist realizes that this unassailability is ultimately a ruse. Recall the Lovecraftian protagonist who is driven mad and shrieking into plutonian night by alien knowledge. This does not mean that the revelation itself is too terrifying to bear, but precisely that the protagonist cannot sanely conceive of the implications arising when the Big Other is finally forced to confront this knowledge unmediated. To wit, the Lovecraftian protagonist only keeps the unknown from public knowledge only to prolong the perverse gratification he receives from indulging in the fear of the unknown. Likewise, it is the insane and perverse royalist who cannot let the Big Other come face to face with the naked truth concerning the monarch. And since they themselves lack the creativity to moderate reality, they should be heavily taxed for the satirist’s thankless public service of humor and cynicism.

Perhaps Bierce had the devil’s definition of the exile in mind when, in the twilight of his life, he decided to travel further south after a tour of his old battlefields and himself disappeared without a trace in the thick of the Mexican Revolution. Because of the looming threat of World War I, only a minimal search effort was carried out, and all that was ever heard of Bierce’s final days came from local legends and campfire corridos3. And though no bones lie beneath his cenotaphs, I like to think that there is some truth to the story of the old gringo who fought and died graveless in the field of Ojinaga.

Exile, n. One who serves his country by residing abroad, yet is not an ambassador.