Don’t say that “Isan” is a term that subjugates the region to Bangkok

When people say “Isan” means Northeast of Bangkok, don’t believe them. While “Ishan” does mean “Northeast” in Sanskrit, it doesn’t have to be relative to Bangkok. Have you ever heard of Emperor Ishanvarman and the Empire of Ishanpura, which reigned over these lands from the 12th to the 18th Buddhist centuries? The term “Isan” mirrors that ancient kingdom, also known as the Chenla Empire. The Empire left its mark with many awe-inspiring stone Khmer temples stretching from Kanchanaburi to Buriram in Thailand to parts of Laos and Cambodia!

Do say that “Isan” is a term that subjugates the region to Bangkok

When people say “Isan” means Northeast of Bangkok, it is true, obviously. Have you ever heard of Emperor Ishanvarman and the Empire of Ishanpura, which reigned over these lands from the 12th to the 18th Buddhist centuries? Me neither.

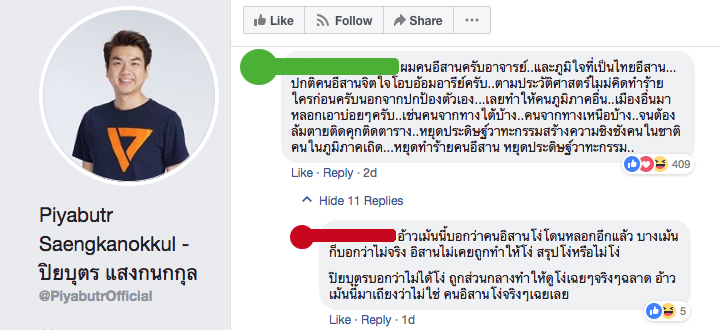

Don’t say that Isan people have been victimized by the government

We have been taught by our family to grow up to become chao khon nai khon, and that means high-ranking officials in the Royal Thai Government. To push victimhood on to us is to deny our agency and ability to gain access to state power.

Those of us who believe in democracy are not necessarily socialist sympathizers. Let me share with you a moment from my days doing an ethnographic field research in an Isan village: a self-identified Red Shirt villager in his 70s that I was on good terms with recoiled when I talked to him about Tiang Sirikhan, a People’s Representative from Sakon Nakhon who was assassinated in 1952. He interjected: “But that’s a communist, no?”

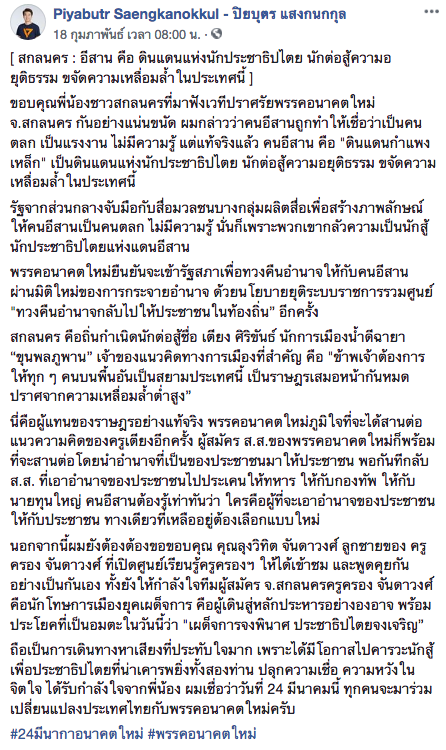

Secretary-General of Future Forward Party Piyabutr Saengkanokkul, take note. To say, as you said in a recent Sakon Nakhon speech which doubled as a hagiography of Tiang Sirikhan, that

“Isan people are made to believe that they are clowns, laborers, and people without knowledge”

is to suggest that we’ve been duped into buying into stereotypes of ourselves, when some of us aren’t even aware that those stereotypes can be used as blanket statements to refer to all 20+ million Isan people. Your speech also suggests that to be clowns or laborers is inferior to or incompatible with being fighters for democracy, which is NOT true.

Do say that Isan people have been victimized by the government

We have been trained by school and society to be aware of who we are on the social hierarchy, and in order to climb it we learned to code-switch and to conceal our origins because the expression of regional or ethnic difference still invites ridicule and negative associations in many social situations today. We know that in order to earn the recognition of “fighter for democracy” or whatever greatness we aspire to, we need to work twice as hard compared to more privileged others.

Kudos to Secretary-General of Future Forward Party Piyabutr Saengkanokkul for pointing this out on an official political platform. To say, as you said in a recent Sakon Nakhon speech which doubled as a call for us Isan people to embrace our status as democracy fighters against injustice and inequality, that

“Isan people are believed to be buffoons, manual laborers, and uneducated people”

is a factual statement about the oppression of our people past and present.

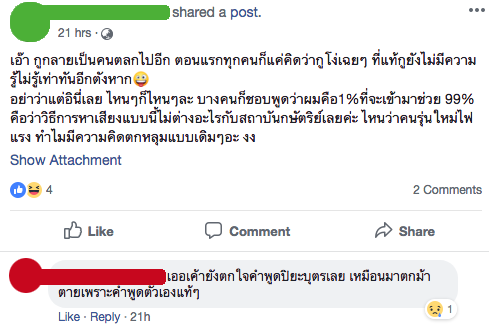

Don’t say that Isan people are gullible

This probably goes without saying. But there’s more to it than just “don’t insult other people.” Sometimes what you say can come across as insult without you intending or even comprehending it.

Imagine yourself visiting a small Isan village, and you’re asked, “so how’s us villagers (sao baan)?” What would you say?

Well, several years ago I was an Isan city kid doing field research in an Isan village being asked that question. A couple of times, I made the mistake of saying, in effect, that Isan villagers are “simpler” (riap ngai) than city folks. I learned that what people in the village wanted to hear was NOT “we are a simple people who lead simple lives.” Rather, they did want to hear that they were friendly (pen kan eng), open-minded, knowledgeable, and genuine.

Simplicity, taken to the extreme, is credulity and defenselessness to more “sophisticated” people. Also, village life is complex as hell.

Do say that Isan people are gullible

As a collective, we see ourselves as genuine and honest people. And sometimes being genuine can cross into being gullible, like what happens to many of our relatives who have gotten so deep in their unthinking devotion to certain political or religious figures. This problem is not particular to us Isan people, of course, but it is a common theme and a big source of tension between generations.

To say that we are gullible, then, is a fair criticism. We should reinforce a culture where we can openly say something others don’t want to hear. We can learn to be more critical of people and institutions we believe in, and less forgiving of those who betray us. So that we may protect ourselves better and gain more from those who don’t have our best interests at heart but who we might still need to rely on.

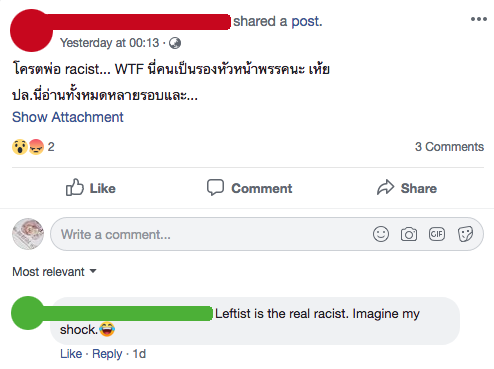

Don’t refer to us as Lao people (or Khmer, or Kuy, or Jek, or whatever the ethnic label at hand)

Here’s a fact: we are Thais, not Laotians. Historical separation from what is currently PDR Laos must mean something, otherwise we can just refer to Taiwanese people whose ancestors migrated from mainland China as Chinese people — no need to say they’re Taiwanese. Too bad that “Lao” as an ethnicity was erased from Siamese censuses, so not only do we now have sanchat Thai (Thai nationality) but also chuea-chat Thai (Thai race).

So, to call Isan people “Lao” when you aren’t Isan (and even to call Isan people “Isan” in certain cases) not only carries the enduringly pejorative sting of the terms. It may also, even with good intentions, go against the way we see ourselves. Some may even think you’re an anachronism (communit long yuk) trying to revive separatism, or worse, a “racist” who’s furthering a divide between us and them (baeng khao baeng rao).

A key nuance here: many Isan people who don’t identify as Lao may still call their language Lao. The most common translation of “Phut phasa Isan dai mai?” into Isan is still “Wao Lao pen bo?”

Do refer to us as Lao people (or Khmer, or Kuy, or Jek, or whatever the ethnic label at hand)

Here’s a fact: we are Thais, and we are Lao. Too bad that “Lao” as an ethnicity has been erased from Thailand, so most of us do not only have sanchat Thai (Thai nationality) but also chuea-chat Thai (Thai ethnicity).

Yet, “Lao” remains a useful category in places like my hometown Sisaket where people of many ethnicities coexist and intermarry. I’ve heard the following anecdote on two separate occasions, yet the same words apply:

“When I first heard he wanted to get married to someone from Buriram, I was worried. Would we be able to understand her family and be on familiar terms? But then we met her family, and found out, with a relief, ‘lao khue kan’ [they’re Lao too!]”

The anecdote ended with the same joyous laughter, even when the person who told it was my paternal grandmother, a Lao-speaking Teochew who understands Kuy!

A key nuance here: “Lao” may not only delineate an ethnic boundary, but also a pan-ethnic cultural milieu that uses Lao as a lingua franca.

Amazing EEE-San!